Photo book review: The Parallel State

Photographer Guy Martin’s new book provides an intimate view of the Turkish subconscious through photographs from Turkish soap opera sets, the 2013 Gezi Park Protests, the 2016 failed coup d’etat, found images, and collected movie posters.

From ‘The Parallel State’ © Guy Martin

Guy Martin was severely injured in 2011 while covering the Arab Spring in Libya. During his year-long recovery, the photographer relocated to Turkey and took a brief hiatus from his work. Six months into his recovery, Martin was itching to return to photography but hoping to capture lighter subject matter than conflict. With the help of a friend, he began shooting on the set of a Turkish soap opera. He continued this project for two years, engaged with the notion that he was getting to know his new home through its world of fantasy and drama.

The result of of this time he spent in Turkey is The Parallel State, published in December 2018 by GOST Books, a London-based independent visual arts and photography publisher. Martin’s photographs from Turkish soap opera sets, the 2012 Gezi Park Protests, the aftermath of the failed coup, and found images, as well as the vintage movie posters he collected, present an unequivocally in-depth view of Turkish consciousness.

From ‘The Parallel State’ © Guy Martin

Martin’s soap opera project coincided with the 2013 anti-government Gezi Park protests. When he started photographing the protests, he tried to avoid his usual style of conflict photography. Then he witnessed a turning point in modern Turkey — and the major event that shaped this book — when a group within the Turkish Military attempted to overthrow president Recep Tayyip Erdogan in the summer of 2016. Erdogan, who has held power since 2003, claimed that this coup attempt was organized by the “parallel state.” In the wake of the attempted coup, what Martin witnessed on the ground was different from what he saw being covered by the Turkish news media.

Throughout his presidency, Erdogan has embraced the idea that a parallel state composed of opposition agents had infiltrated the government and was actively working to undermine his rule. These agents were supposedly followers of Fethullah Gülen, a Turkish cleric on a self-inflicted exile in Pennsylvania, with followers in Turkey and abroad who may number in the millions. This paranoia coming from the most powerful figure in Turkey has permeated all levels of society.

I was born and raised in a small town in southern Turkey. When Erdogan was elected prime minister for the first time, in 2003, I had just started college in Ankara, the capital of the nation. At first his government didn’t feel all that different from its predecessors. It took several years for the stark contrast of his governance to become apparent. Those years were also when a sense of uneasiness emerged among Turkish citizens. Looking through Martin’s book awoke the paranoia that has subsequently become ingrained in the subconscious of most Turkish citizens, even me. The book gives viewer a suspicious sensation that mirrors the current political climate in Turkey. Martin is able to accurately portray this collective anxiety through his seamless transitions between fictional and real-life scenes. At first glance, it is difficult to determine what is truth, making the viewer begin to doubt reality, which leads to a sense of disorientation.

The experience of reading this book mirrors the experiences of Turkish citizens in a post-truth society. When your everyday reality doesn’t match the discourse you receive from the government, you lose trust in both yourself and authority. In other words, a constructed reality is being presented, which leads to self-doubt, altering what you’re willing to believe.

Photos from ‘The Parallel State’ © Guy Martin

The Parallel State uses found images, that are published on smaller and thinner pages, to divide itself into sections. The interventions work as bridges that help the overall narrative flow smoothly. It is also chaptered by a series of photos of curtains, giving viewers the impression that we are progressing through a series of acts. Some are photos of stage curtains, others are of curtains from scenes of everyday life. This visual tool makes it hard to pin down what is authentic as it continues to the blur the lines between fiction and real. For example, a pair of heavy, gold satin curtains opens up to a stage on which we see a broken sculpture of Ataturk, the founder of the Turkish Republic. Under the current political climate this is an unsettling image. It is a challenge to place this image. Is it an image from a soap opera? Or is it from a protest? These possibilities draw you in with anticipation. The curtains also create and contribute to a sense of voyeurism. A female figure is seen through a sheer curtain. You feel as if you are intruding on an intimate moment, in which she is not aware of your presence.

Found photographs of unnamed soldiers from ‘The Parallel State’ © Guy Martin.

A man walking by a car is seen through a curtain of strings. In this case, the curtain creates a divide between the inside and outside world, leading into a section of the book featuring images made indoors. Coupled with photographs of surveillance cameras at sometimes unexpected spots, such as an overlook along the Bosphorus Strait, curtains enhance the unsettling emotional experience Martin puts the viewer through.

These photos recall memories of previous decades of conflict between the Turkish military and the PKK, the Kurdistan’s Workers Party, an organization that is listed as a terrorist group in the region by NATO and the European Union. Families were — and, to this day, still are — worried about their sons completing their mandatory military service in certain parts of the country. For years, many young men didn’t return home. The young soldiers would send these types of photographs as a greeting to their loved ones. One of the photos is engraved with the words “Selam Baba” or “Hello Father.” Such an intimate message leaves us wondering if he made it home to reunite with his family. The possibility he did not is heart-wrenching.

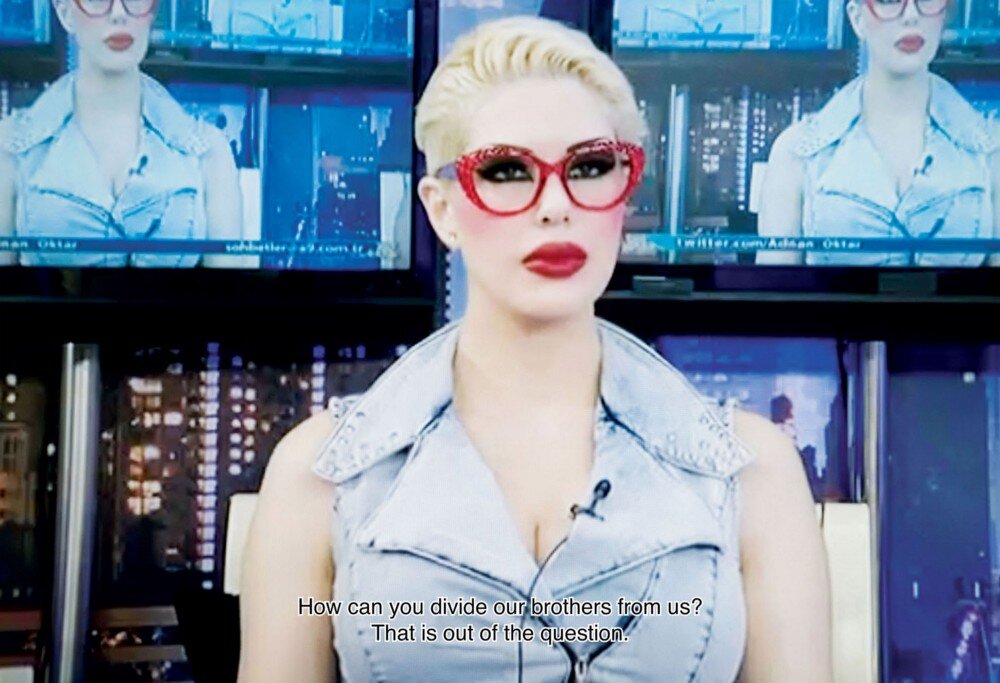

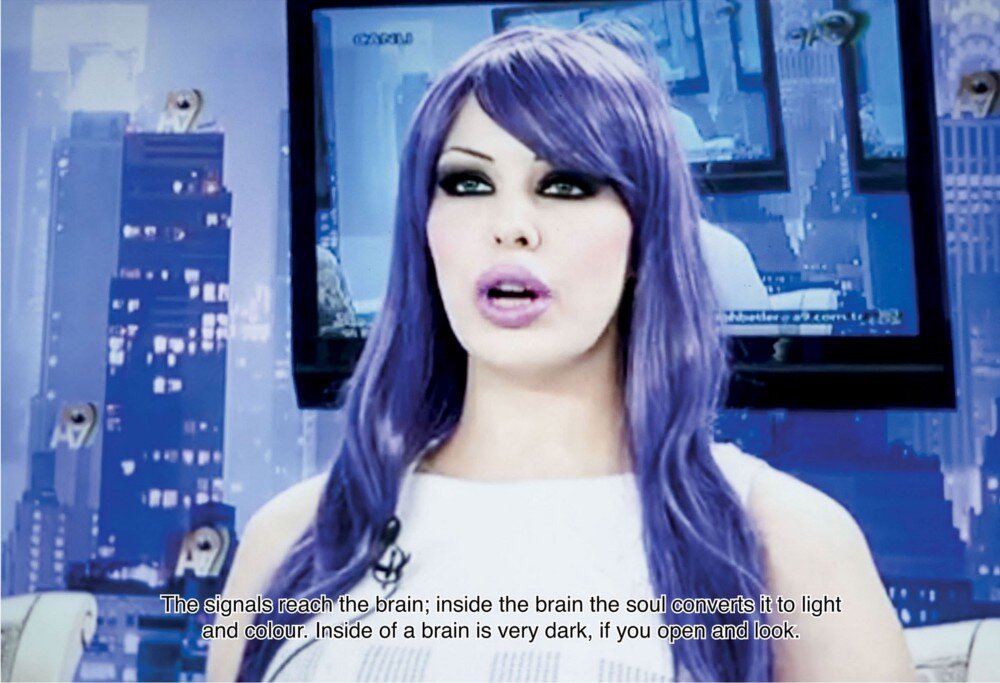

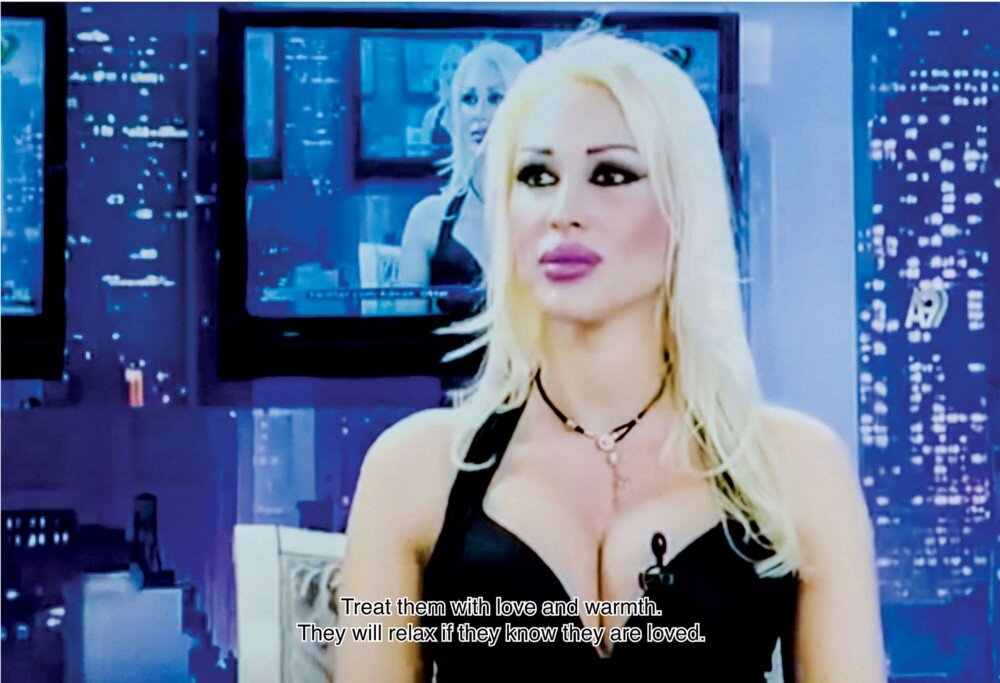

This work is very much a series of juxtapositions. A deeper layer of juxtaposition occurs in the section that features Islamist creationist author Adnan Oktar’s “kittens.” Oktar is known for leading a cult-like conservative congregation. The “kittens” are his female devotees — women who are hyper-sexualized and appear on television to promote his conservative values. Screenshots with subtitles from Oktar’s television show display the “kittens” discussing a variety of topics such as death, politics, and love and compassion within Islam. Their appearance is in such contrast with the values they speak of that it’s hard to reconcile their existence. Yet, the “kittens” fit well into this book because it’s hard for an outsider to believe they are real. But even the discombobulated existence of the “kittens” finds its place in contemporary Turkish society.

“Unsettling” is a word that kept coming to mind as I turned the pages of Martin’s book. Perhaps the most troubling part is the transcription of a WhatsApp chat among the individuals who attempted a coup on the night of July 15, 2016. Reading the progression of the events in that way — from a night that terrified millions living in Turkey and abroad — felt more real yet surreal than ever before. The transcription provides some context for what follows in the book, a section of bright images, such as a scorpion on a completely white background and a photo of a man running along a dusty road in broad daylight, followed by dark, eerie, and sometimes gruesome images from conflict in the streets. In a book where conundrum between fiction and reality is ever-present, the authentic moment of the WhatsApp chat is one of the rare opportunities to experience clear reality in stark contrast with the rest of the book.

It is impossible to ignore the way color, toning, and light are used in The Parallel State. Martin consciously shied away from the visual style he had used previously in photographing conflict. “I was getting to know a country through its drama and fictional storylines instead of its conflicts,” he writes. “I was changing as a photographer too — immersing myself in a version of reality; a parallel state of mind. I found a new way to relate to the medium I loved by spending time in a fictions world, full of fantasy and drama.” Inspired by the soap opera sets with controlled lighting, Martin occasionally makes use of flashlights. One strong example shows an extremely overexposed image of a protest scene. The heavy lighting somehow manages to obscure the individuals, enforcing dubiousness and collective anxiety. Martin’s visual language swings between saturated photographs with dark and warm colors shot under available light to photographs with cooler, desaturated colors shot under heavily controlled lighting. All the visual tools provide a thread to unite the discourse of this project.

The strength of this book lies in its ability to visualize an emotion and make its viewer strongly experience that feeling through narrative. Martin pinpoints a feeling that is so vague in contemporary Turkish society, yet would be immediately recognizable to someone within it. This is a bizarre book — and a great representation of the bizarre times Turkey is currently experiencing.

Photos from ‘The Parallel State’ © Guy Martin

Pinar Istek is a Turkish freelance photographer based in Chicago. She regularly collaborates with editorial clients and, in her personal projects, focuses on issues related to race, ethnicity and gender. She is a Ph.D. candidate in journalism at the University of Texas at Austin. Follow her on Instagram.

The Parallel State by Guy Martin is published by GOST Books and available for purchase here.