The impact of photography amidst the extinction of the mass media

Danielle Jackson examines the limits of diversifying the field of photography in an age of fragmented media.

“More like this:” Pinterest images recommended to the author by customization algorithms.

A few years ago I began making screenshots of my friends’ posts on Facebook. Rarely did the photos, videos, or memes from any of these respective worlds overlap; I couldn’t even find a point of convergence. My feed sat at the nexus of a few distinct communities—white folks from my working class hometown; black family members in the suburbs; radical activists in Brooklyn; survivors of homicide victims; media professionals — and quickly I realized that each of these groups was living in a vastly different image ecosystem. Though “filter bubbles” are usually described in terms of political polarization, alienating the left from the right, what I found was far more personalized. Images from the world in which I worked, documentary photography, figured precisely nowhere into these feeds, and constituted a rapidly expanding bubble of its own.

In recent years a number of initiatives have emerged to promote the work of photographers from groups that are underrepresented in the industry. The unfortunate paradox is that serious attempts to include marginalized perspectives in photography are taking place at a time when it is unlikely the work will ever be seen by broad audiences. (This is almost as sad an irony as is the fact that inroads at diversity have arrived after all the good money has gone.)

Although more than a billion photographs are uploaded and shared daily via platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, and WhatsApp, documentary photographers no longer publish in a communal environment to captive mass audiences. A diffusion of attention undermines their ability to shape public opinion through their work. Some of the same platforms that have facilitated greater diversity in the field, allowing unrecognized photographers and gatekeepers to forge new relationships, have filtered the world into innumerable information factions. Narrowcasting (as opposed to broadcasting) has quickly become the new norm. “My children will certainly never, ever understand this concept of mass communication,” said Alexander Nix, CEO of Cambridge Analytica. (Nix was recently suspended in the wake of the organization being placed at the center of the scandal for tailoring political ads using psychological profiles gathered from Facebook data.) Audiences have become smaller, discrete, and seemingly more like-minded. Understanding this landscape is crucial to any discussion of diversity in the media. While it is high time photography became more inclusive, it’s unclear who will see the perspectives of these formerly marginalized talents.

The trouble, as we’ve learned from the recent Facebook scandals, is that capitalism has developed in new ways that keep people from receiving the same information. The surveillance economy, a multibillion dollar industry that extracts and monetizes personal data, has helped fragment media consumers through its practices of tracking, micro-targeting, and hyper-personalized recommendation. The material collected, amassed from dozens of data points about a person’s interests, location, and browsing habits, exceeds the customary demographic information such as age, race, or gender. By monitoring users’ activity online and merging it with data from real-world behavior, such as offline purchases and telephone calls, marketers and publishers have the necessary information to place content based on its perceived relevance to users. These practices, used by Google, Facebook, Instagram, and others, have splintered audiences, possibly beyond repair.

Psychographics of the New York Daily News and Rolling Stone that measure their viewers’ financial behaviors, health and well being, “greenaware”ness, and media involvement.

Many photographers still rely on the validation and distribution that comes with legacy media. Although these outlets can be powerful amplifiers, they no longer reach as many people as they once did. In a nation of 327 million, few U.S. magazines circulate more than 3 million copies. American audiences have shrunk in part because attention is spread across numerous platforms that compete for influence. The top-rated network television shows have only 18.5 million average viewers, roughly 15 million fewer than in 1996 (although there are nearly 60 million more people in the country). Cable news channels reach no more than 3 million people during primetime. At the end of 2017, print and digital subscriptions to the New York Times totaled 3.5 million worldwide. By contrast, LIFE magazine had 7.5 million subscribers when Gordon Parks published his essay on an impoverished Harlem family in 1968.

Digital traffic commands significantly larger figures, but those numbers do not amount to sustained engagement. Even though the online edition of the New York Times received roughly 89 million unique visitors per month in 2017, most are casual viewers who do not have a subscription and spend just five minutes on the site fewer than ten times per month. At The Washington Post, 85 percent of their roughly 89 million unique visitors per month do not read more than three articles per month. In January, Facebook announced a major shift to its algorithm that would limit the material posted by media organizations, thus weakening what had become useful amplifiers of all forms of journalism, including documentary photography projects.

The demise of traditional media has occurred alongside a proliferation of digital publications and blogs devoted to photography, but these sites have a limited reach. While looking at documentary photography online, one may have the feeling that photographers are mostly publishing for each other. A few companies do exceedingly well. National Geographic, which has more than 350 million combined followers across its social media platforms globally, is the most popular brand on social media. But most have far fewer followers. Across their social media platforms, Time’s LightBox has about 800,000 followers, while The New Yorker’s Photo Booth has almost 620,000. In recent months sites like Magnum Photos and LensCulture, which cater to photographers and other creative professionals, typically reached fewer than 400,000 unique visitors worldwide per month each, according to analytics service SimilarWeb. While a tiny handful of photographers have more than 1 million followers on Instagram, many more have fewer than 100,000. Though these are considerable numbers for an individual to accrue, they do not amount to a broad public.

SimilarWeb results for traffic on MagnumPhotos.com.

Bubbles can feel deceptively universal. Photographers must get a sense of the silos in which they are already publishing; this includes understanding the traffic and demographics of the larger platforms that show their work. Even some of the most discussed images in recent history may not spread as evenly as we may want to believe. According to a 2016 survey from Pew Research Center, black social media users report seeing posts concerning race nearly two times more often than white users. To my surprise, just two of the nine college students I taught this winter had seen the 2015 image of Alan Kurdi, a Syrian boy washed ashore in Turkey.

Though some people will encounter the work of underrepresented photographers through books and exhibitions, many are bound to be directed to photography projects through the kinds of algorithms designed to present users with more of the same material they have already seen. As many resort to tribalism, people appear incurious about the worlds beyond their subculture. The element of discovery has been replaced by burrowing deeper into the knowledge of the groups one already knows. If they had the will, a person could search for projects that disrupt their worldview, but search results are also tailored in part by personal browsing history and other factors. As platforms including Facebook and Twitter use sentiment analysis (artificial intelligence tools that interpret emotional tone) to create “positive” and “healthy” experiences, I worry they may deemphasize documentary photography projects on the basis of their sometimes serious subject matter.

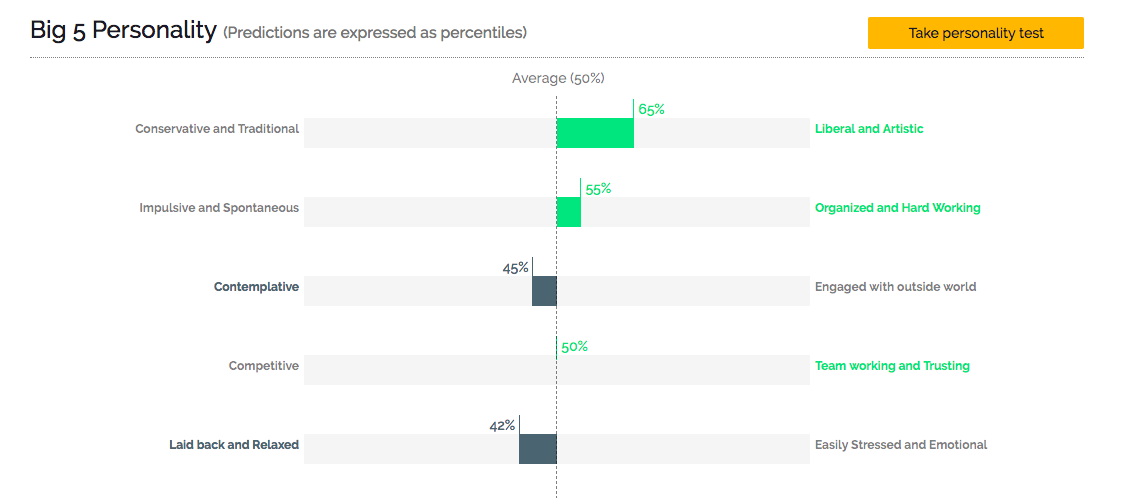

The author’s “Big 5 Personality,” according to her posts on social media, analyzed by Apply Magic Sauce.

This factionalization experienced online is formed in large part by our behaviors. Social integration seems rare. In a study published by Science in 2015, researchers found that our selection of friends and the material we click are more responsible for creating political bubbles on Facebook than algorithms. Anyone building an audience will be constrained to some degree by their pre-existing network. Though it may be possible to build a fairly sizable audience, it would be impossible for an individual photographer to build an audience as diverse as what legacy media had in its prime. Recently, I asked photographer Josué Rivas, who is building a website to shift the public’s perception of Native Americans, “Would this project reach my grandmother?”

Not only do these practices mean photographs are more likely to be distributed within networks of like-minded people, but also they may never be seen beyond the audience an algorithm defines. Despite the constraints, I still meet photographers who, upon being asked who their intended audience is, will reply, everyone. It is disheartening to meet these photographers who are enamored of the photograph’s bygone ability to influence national conversation, who dream of large-scale social impact, or challenging mainstream depictions of this group or that — when in all likelihood only a select number will see their work. If self-segregation continues, and divisive algorithms prevail, I fear photographers from underrepresented backgrounds will once again go unheard, publishing for small communities and gaining no wider audience. I worry that these silos feed the perception that nuanced stories aren’t being produced when they are merely hiding in plain sight.

These problems seem irreversible in a surveillance economy. But there are some imperfect strategies photographers can adopt to work within these parameters. The required adjustments photographers must make are as psychological as they are tactical. This means using new language, revising ambitions, and identifying personal standards by which to measure impact. What does it mean to produce work if it is not likely to effect a mainstream? Photographers will have to learn how to produce for smaller, targeted audiences who will actually review the work, or devise new approaches to reach larger audiences outside of their bubbles.

First, photographers who create their own platforms must have a specific audience in mind, and a strategy to cultivate them, from the beginning. Before building expensive and time-consuming digital projects, photographers need to be honest with themselves regarding user engagement. How many page views or visitors will make them happy? Aside from mastering video making, grant writing, and other demands placed upon them, photographers will have to behave as marketers and publishers — partnering with experts in search engine optimization, market segmentation, traffic flow, and other media engagement statistics in order to understand who their work is reaching. If the movement for data ownership comes to fruition, analytics tools that track many types of data may be rendered useless. But in the meantime, to ensure photographers are reaching beyond a bubble, it will remain important that robust controls are available that measure metrics that account for demographic details such as age and region — along with other, more sophisticated data, like scroll depth and referral traffic from social media.

Photographers can also be more collective in their efforts toward distribution. Since documentary photography has lost primacy among videos, memes, and other forms of content, photographers should consider coordinating with other visual producers to multiply their reach. The alt-right’s influence is due, in part, to a kind of sustained cultural production on the part of a relatively small number of individuals’ collective efforts to create and circulate images. There is a lesson to be learned here. I see two options: photographers can play to their base and forge alliances with influencers in adjacent, like-minded silos; or they can make concerted efforts to partner with platforms that reach wildly diverging types of people.

Documentary filmmakers, accustomed to addressing small audiences, have started to work with impact producers to connect their films to local change campaigns. Photographers may wish to take a cue from that world. Esther Mbabazi, a photographer and Magnum Foundation fellow from Uganda, with the help of Kiersten Nash, an experience designer, created a multi-phased plan to transform her project on the neglect of older adults into a guerrilla advocacy campaign. After identifying her target audience and mapping the places they congregated, Mbabazi and Nash created a logo, messaging, and set of images to post throughout Kampala, which will direct people to an online call-to-action. Ana Brigida photographed people living with toxic mold inside New York City’s public housing. Though the work was published by the New York Times, the New York Daily News, and VICE, the true achievement was through her partnership with Manhattan Together, a local organization which used the photographs at public hearings and during its settlement of a class-action lawsuit against the city. Michael Premo’s exhibition and short film Water Warriors chronicles a Canadian community’s successful fight to halt drilling and win a moratorium on fracking in their province. Premo, a former organizer, exhibits the work in communities that are waging similar efforts, and leads local groups in strategy sessions at the site of the exhibition.

Photographers from underrepresented groups are often concerned with changing the dominant culture, but they might consider expanding their idea of who stands to benefit from seeing their work. Consider Elias Williams, an emerging photographer who seeks to acknowledge the stories of African American homeowners in a historically black suburb in Queens. Upon seeing Williams’s work, white photographers told him they had never before seen images of the inside of a middle-class black home. But neither, really, had my barber, a 30-something African American renter who works 10 minutes away from where Williams lives in the South Bronx. “The Cosby Show,” he reminisced while I sat in his chair last summer, “was the only place where we saw that we could own homes.” What if Williams’s work appeared in my barber’s Instagram feed or other sites that he browses? What might a distribution plan look like that includes this neighbor? The subconscious impulse to have “the world” (along with their colleagues) interact with their project usually changes how and where it is presented.

The former home of world heavyweight boxer, Joe Louis, and his second wife, Rose Morgan in St. Albans, New York, 2014. The pair had their wedding ceremony in the home on Christmas Day in 1955.

Tasha Stoudymire and her daughters, Amani and Asadah in St. Albans, New York, 2014. Tasha is a photographer who also runs her own after-school program, Joy in the City After School, in the community. Photos by Elias Williams, @elias.williams

At the turn of the century, upon learning of the shifting demographics in the U.S., many optimistically believed a new population would constitute a large, united viewing bloc comprised of formerly marginalized voices. Instead, Americans have scrolled and parceled our way into a kind of media pluralism. Audiences for photography might go the way of television’s, where people watch completely different programs depending on the micro-culture to which they belong. Nearly 40 percent of the people living in the U.S. are members of minority groups, and most babies born in the U.S. are no longer white. We once held high hopes for this generation; we imagined they would possess a greater sense of empathy, coalition, and cultural fluency than did the generations before them. But when the flow of information has become so personalized, audiences so segregated, and photography so siloed, I’m not sure they can ever fulfill that promise. How many Americans will continue to drift away from each other, seeing little of the world around them, in ecosystems of their own very specific image?

Danielle Jackson is a fellow-in-residence at NYU’s Center for Experimental Humanities and the co-founder and former co-director of the Bronx Documentary Center. She has worked with leading photographers, filmmakers, and cultural institutions to develop projects, partnerships, and initiatives for social impact. Follow her on Twitter.